I steeled myself before streaming Anna Deavere Smith’s “Twilight: Los Angeles” on PBS.

I knew the film, based off her one-woman play, “Twilight: Los Angeles, 1992,” about the unrest following the police beating of Rodney King, would make me, as a white person, feel more keenly, more viscerally, how little has changed for Black Americans in 28 years.

I also knew that Smith’s embodiment of 40 real-life characters, in all their vocal, physical and facial tics, created from 300 interviews she’d conducted, would dazzle me in its technical precision. I anticipated that the sheer variety of perspectives represented — activists, police officers, lawyers, politicians, artists, shopkeepers; Latinos, Koreans, Blacks, whites — would evoke, as few other media could, just how endlessly complex this painful moment in our country’s racial relations was, how far-reaching its implications were.

But I didn’t anticipate that the gut punch would come before the docudrama itself started.

In her introduction for PBS, where you can stream the show through June 2021, Smith cites current events as a factor in the decision to rebroadcast: “In light of the challenges facing our country right now, I hope that this encore presentation of ‘Twilight’ offers some lessons learned in Los Angeles and that they can be applied now.”

Apt as that introduction is for our era, it was filmed in 2015, not 2020. Smith was responding to the death, in police custody, of Freddie Gray and its aftermath.

I wondered if we’re doomed, each time a Black citizen dies another senseless death, to look to Smith for answers to the same question — or whether this moment was different.

“我不知道我能说结果be different, because I don’t have a crystal ball,” Smith tells me by phone. But she does see differences between the recent resurgence of Black Lives Matter activism, following the death of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others, and what she observed in her extensive study of Los Angeles in 1992. There was more destruction then, she says, and there was an additional layer of complexity with the Korean American community, following the killing of Latasha Harlins.

But in our time, “it’s relevant that it happened during the pandemic,” she says. Additionally, “the protests are worldwide,” in a way that they weren’t almost 30 years ago. She thinks young people’s concerns about climate change, about student loans, about health care, about the presidential election, “all fed into the streets” in 2020’s demonstrations. Los Angeles didn’t become a movement, but our moment “may be” one, she says — especially given previous Black Lives Matter activism.

年代mith has had “Twilight” in the forefront of her mind in preparation for a Signature Theatre production that had been scheduled to begin performances in New York in April, performed not by her but by five other actors. Asked if any particular characters seem to speak to our time, Smith first mentions Rep. Maxine Waters.

In a speech in the film, performed verbatim (as she does in all her docudrama), Smith as Waters says, “We had an insurrection in this city before, and if I remember correctly, it was sparked by police brutality. We had the Kerner Commission Report (which studied the causes of 1967’s racial unrest) and as I stand here today, in 1992, I see that what that report cited still exists today.”

Reflecting on that moment, Smith says, “I don’t want to say too much, because I’m older than a lot of people who are on the front lines now, and they should be on the front lines. But it’s like, OK, here we are, 27 years later. And that was 30 years ago. So that makes this almost 60 years. And we know that it actually goes back centuries, this kind of abuse.”

年代mith also thinks about the character of a police officer in Los Angeles’ special weapons and tactical unit, who laments that the reason the police had to beat King was that they weren’t allowed to use a choke hold any more — the implication being that it’s a more efficient method of suppression.

“It’s not about the choke hold,” Smith says. “It’s about the force itself. If the way you were controlling people was just to put toothpicks in their shoulders, too many toothpicks could kill them.”

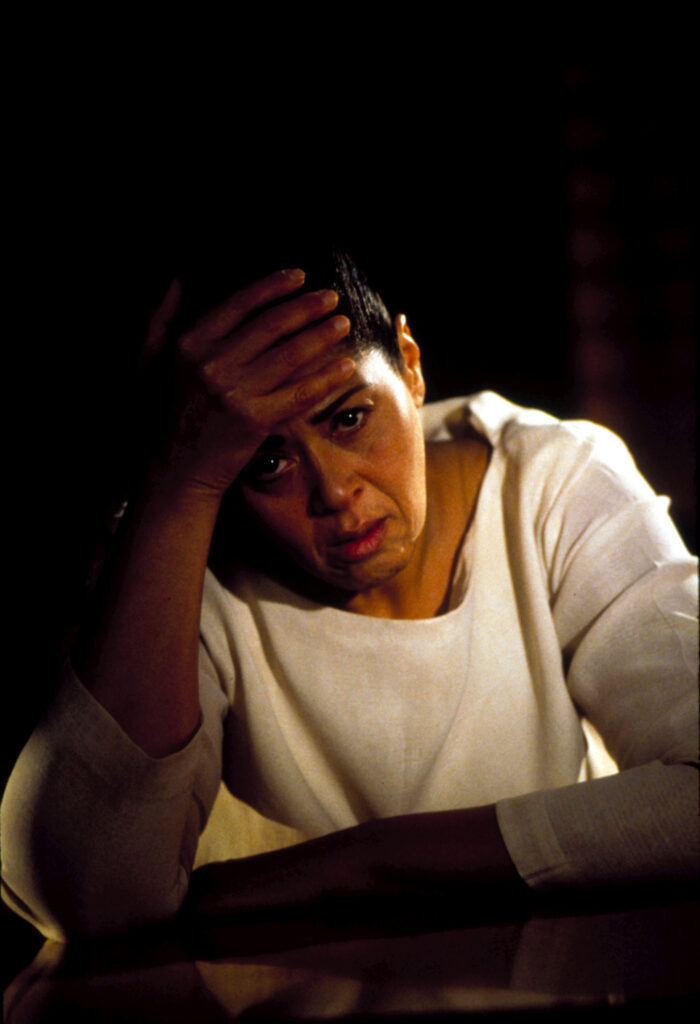

To watch Smith take on her characters is first to witness rigor on broad display. Her sundry voices spike and squawk and snarl. One character seems to speak by pushing words through the crack in her front teeth. Another’s mouth seems to lie slack except for one invisible, askew clothespin holding it up. A third seems to have a bubble in the back of the throat, as if the body itself scruples to speak.

年代ometimes you might think you see Smith herself sneaking through to comment on her characters as she performs them — a glint in the eye, a corner of the mouth creeping upward. But just as often, the transformation is total. In those moments — when a Korean immigrant asks why a loved one had to die — the enormity, the thorniness, the impossibility of it all hits you. Each of these characters is speaking perfectly reasonably, given their life, their background. And yet none of them can see the whole thing; everyone’s lens has myopia, distortion.

“I want to talk differently than I talk,” Smith says. “It’s not that interesting for me to perform people who are just like me.

“The way that I’m working is a response against psychological realism, which is this belief that I live in every character. I understand I’m very different from every single person I’m performing. I’m chasing that which is not me. I know I could never be it. It’s more like singing a song. I’m hitting the notes.

“Every once in a while — when I can’t expect it; it has nothing to do with my mind — that person’s words knock on the door of my unconscious. And it’s kind of scary sometimes when I’m on stage, I’m like, ‘Oh my God, I did have an experience kind of like this!'”

“Twilight: Los Angeles”:Docudrama. Written and performed by Anna Deavere Smith. Directed by Marc Levin. (One hour, 27 minutes.) Available to stream atwww.pbs.org到2021年6月8日。